(Illustration by Anthony Russo)

(Illustration by Anthony Russo)

The New York Times | The Opinion Pages

By ALEX DE WAAL

On one of the last occasions an Egyptian president visited Addis Ababa, he got no further than the road from the airport: In 1995 the motorcade of President Hosni Mubarak came under fire from Egyptian jihadists. Mr. Mubarak was saved by his bulletproof car, his driver’s skill and Ethiopian sharpshooters.

After that, Ethiopian and Egyptian intelligence officers worked together to root out terrorists in the Horn of Africa, contributing, along with pressure from the United States government, to Osama bin Laden’s expulsion from Sudan in 1996. But that was the limit of their cooperation.

Egypt and Ethiopia have otherwise been locked in a low-intensity contest over which nation would dominate the region, undermining each other’s interests in Eritrea, Somalia and South Sudan. A quiet but long-sustained rivalry, it is one of those rarely noticed but important fault lines in international relations that allow other conflicts to rumble on.

This week, however, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi of Egypt is expected to fly to Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, to attend a summit of the African Union. He will also meet with Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn of Ethiopia, a rare chance to shift the political landscape in northeastern Africa.

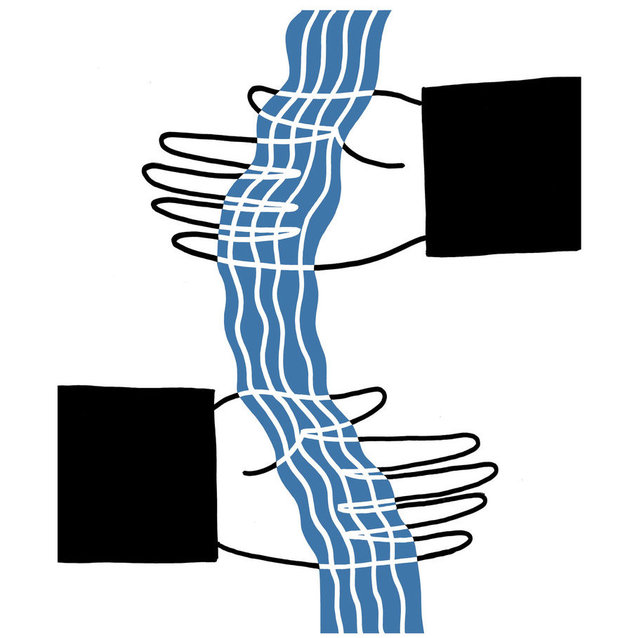

The heart of the rivalry hinges on how to share the precious waters of the Nile River. Running low is Egypt’s nightmare, and more than 80 percent of the Nile’s water comes from rain that falls on the Ethiopian highlands and is then carried north by the fast-flowing Blue Nile. (Ethiopia is nicknamed “Africa’s water tower.”) Yet management of the Nile is formally governed by a 1929 treaty between Egypt and colonial Britain, and a 1959 treaty between Egypt and Sudan that awarded most water rights to Egypt, some to Sudan and none explicitly to Ethiopia or the other states upstream. This arrangement is widely considered unfair, especially to Ethiopia, which was never colonized, and on whose behalf Britain could not even claim to have spoken. This legal framework also limits the right of upper riparian states to build dams or irrigation systems even though they were sidelined from helping shape it.

Read more at NYT »

—

Join the conversation on Twitter and Facebook.