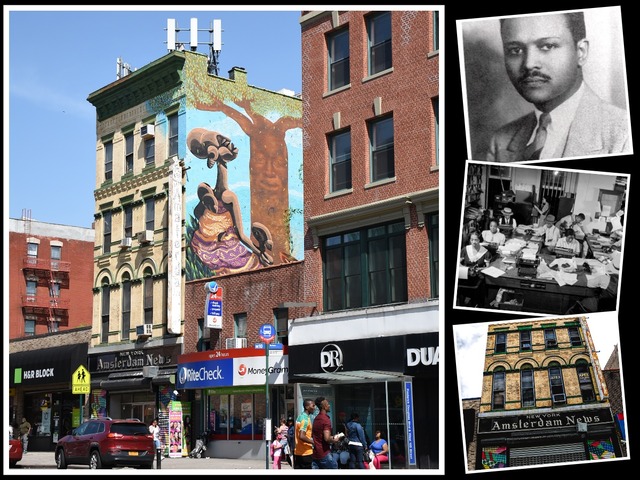

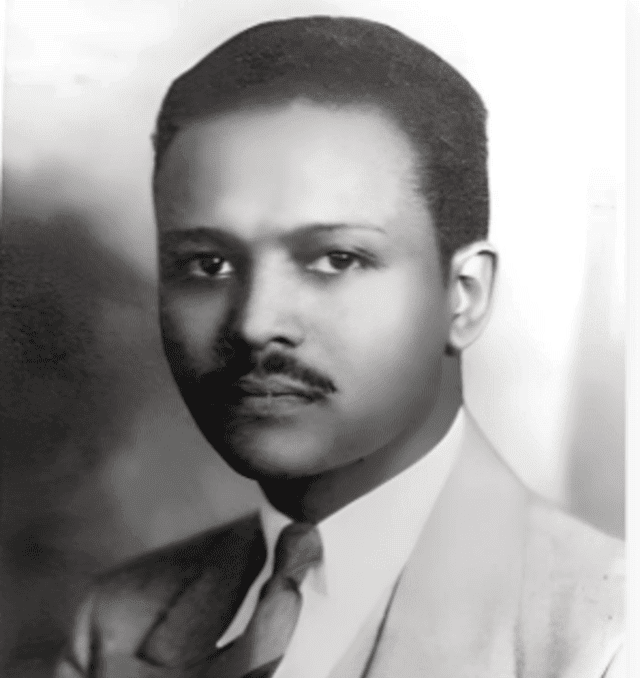

Dr. Malaku E. Bayen: A Pioneering Voice for Ethiopia and the Global Black Community. (Photo: Tadias file)

Dr. Malaku E. Bayen: A Pioneering Voice for Ethiopia and the Global Black Community. (Photo: Tadias file)

Tadias Magazine

Publisher’s Note:

As part of our Black History Month highlight, Tadias is honored to present this insightful article by Dr. Fikru Negash Gebrekidan, Professor of History at St. Thomas University in Canada and author of Bond without Blood: A History of Ethiopian and New World Black Relations, 1896-1991. In this exclusive piece, titled From Ethiopia to New York: A Gandhian Moment in Ethiopian and African American Encounters, Dr. Gebrekidan examines a pivotal yet often overlooked moment in history—Dr. Malaku E. Bayen’s arrival in the United States in 1936 and the defining experiences that shaped his advocacy.

Drawing parallels between Bayen’s journey and Mahatma Gandhi’s formative years in South Africa, this article highlights a turning point in Ethiopian and African American connections, revealing how moments of adversity sparked new possibilities for leadership, solidarity, and global engagement.

We are grateful to Dr. Gebrekidan for his meticulous research and contribution to this important and timely conversation.

— Liben Eabisa, Publisher, Tadias Magazine

—-

A Gandhian Moment in Ethiopian and African American Encounters

By Fikru Negash Gebrekidan, Ph.D.

February 11th, 2025

TADIAS – Among the arrivals at Ellis Island on 23 September 1936 was a family of three Black refugees: Dr. Malaku E. Bayen, his wife Dorothy Hadley Bayen, and their four-year-old son Malaku, Jr. Although Italy’s genocidal war on Ethiopia was the reason for their flight out of East Africa, first to Britain and then to the United States, the Bayens were not ordinary refugees. With Emperor Haile Selassie’s appointment of the physician as his personal envoy to Black people in the Western Hemisphere, the Bayens came to New York City as de facto extension of the exiled Ethiopian government, making them a proxy of the ancient African monarchy.

Born in 1900 in the Warrailu district of Wollo, Malaku grew up in Harar and Addis Ababa as a distant cousin in the large Ras Tefari household. In 1921, following a failed scholarship trip to India, he moved to the United States to study chemistry and medicine, and during which he married Dorothy Hadley of Howard University. When Italy invaded Ethiopia in October 1935, he served as a medical doctor both in the eastern and northern fronts; and had it not been for the emperor’s controversial decision to form a government in exile, he would have continued the resistance from Gore, the makeshift capital in the southwest after the fall of Addis Ababa. Yet, nothing prepared Malaku for his experience in New York on the fateful day of September 1936, which was reminiscent of the life-changing event that Gandhi encountered at a South African train station four decades earlier.

Ahead of the Bayens’ arrival, a reservation had been booked at the Manhattan Hotel Delano by Dr. Philip Savory of the United Aid for Ethiopia (UAE). On the morning of 23 September, the guests were picked up from the liner St. Louis by the West Indian Savory, and then driven to Delano at 108 West 43rd Street, where the rest of UAE’s executive board members were waiting. Like Malaku, Savory was a medical doctor by profession, but it was because of his integrity as co-owner of the New York Amsterdam News, Harlem’s leading Black Newspaper, that he was entrusted with the role of UAE treasurer. The other board members included Cyril Phillips, UAE organization secretary; Rev. William Lloyd Imes, pastor of St. James Presbyterian Church; and Theodore Bassett, labor organizer.

Introductions must have remained perfunctory, for all but one of the committee members were known to the Bayens from a previous encounter in Europe. That was in early August 1936, when Savory, Philips, and Imes visited Emperor Haile Selassie at his exile home in Bath, England, in their capacity as UAE representatives. Since Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia a year earlier, American cities had experienced a flurry of fundraising activities by imposters, prompting certain respectable voices of Harlem to come together and form the United Aid for Ethiopia. In Bath, the UAE delegates would impress on the exiled king of the need to bring the disparate relief efforts under a credible central leadership, which was how the unique family of the Bayens was handpicked for the said mission in North America.

Then & Now: The New York Amsterdam News – A Legacy of advocacy journalism in Harlem and a historic platform for Black voices and global connections. (Photo: Wikimedia and Amsterdam News)

The scene at Delano began with the Bayens having to wait until their room was made available, not an unreasonable request during busy hours of the day. Afterall, as a sign of courtesy, a hotel porter was sent to the liner to fetch the passengers’ bags. What the guests did not know, or pretended not to notice, was the consternation felt by the desk clerk the moment they presented themselves. After two hours of limbo, they learned from the chief clerk Frank Mazetti that the hotel was fully booked. Questions why the reservation was not honored, or how a porter could have been sent to the harbor in this case, produced inconsistent answers: the family suite was already rented; or it was being painted and the guests had to wait; or it was being painted but may not be ready anytime soon. After more hours of waiting, by which time Mrs. Bayen and Malaku, Jr., had left for the Savory’s by cab to rest and freshen, Mazetti would resort to a more subtle tack. He offered a single room on the eleventh floor and another on the mezzanine, which the family of three was bound to find unworkable.

What should have been a routine business transaction had thus dragged into a long, drawn-out spectacle. Lawyers from the powerful International Labor Defense, ILD, as well as activists from the Harlem’s All People’s Party had converged at the scene by late afternoon. Picketing and boycott options against the Delano were considered, and papers were contacted to make sure that the civil rights violation did not go unreported. The day concluded with the Bayens having settled in the nearby Rex Hotel, 106 West 47th Street, which would double as family lodging and makeshift office for the next several weeks.

Dr. Malaku E. Bayen. (Photo: Tadias file)

Once the scandal leaked into the media, Delano denied flatly the Jim Crow accusation. Later, its explanation shifted to the fact that the Bayens were registered as prince and princess. Some time back, a Broadway fixer had schemed with a little-known Harlem showwoman, Islin Harvey, promoting her to clubs and the media as a native Falasha princess turned a globe-trotting artist. With that farcical scandal still in memory, the hotel staff insisted that Prince Malaku and Princess Dorothy were turned away because their aristocratic credentials seemed contrived. The alibi convinced few. Even if de guerre segregation was absent north of the Mason-Dixon, it was common knowledge that white establishments fell back on unwritten social codes to turn away Black patrons.

While Malaku rejected any legal recourse so as to stay focused on his fundraising mission, the public uproar took a life of its own. Harlem’s All People’s Party wired a strong message to the State Department, demanding for an appropriate redress for the insult suffered by a foreign dignitary. Even as he advised that the matter be taken up with local authorities as the victim bore no formal diplomatic status, Secretary Cardell Hull expressed regrets over the “discourtesy.” Hull’s response, while outwardly neutral, gave the scandal a national recognition that other actors could not easily ignore. The American Labor Party, an inter-racial group affiliated with the Democratic Party, transferred its county convention on 11 October from Delano to Labor Stage Theater, 106 West 39th Street. The Federation of American Musicians followed suit, choosing to sever any business ties with the now disgraced establishment. By years end, the struggling hostelry had rechristened itself as Hotel Center, a plain sounding name without a controversial history.

For the Bayens, too, the hotel rebuff had transformative consequences. It was where and when Malaku’s preoccupation with fascism began to shape into a broader and more militant cause of global anticolonialism. The liberation of Ethiopia from Italy was no longer an end in and of itself, but a vital component of the international struggle for racial justice and colonial freedom.

A few days after the Delano low point, Malaku’s first public appearance at Rockland Palace would attract over two thousand residents of Harlem, a prelude to extensive travel and countless lectures nationwide. With Malaku as vice president and Pastor Lorenzo King of St. Mark’s Methodist Church as president, the various aid groups would merge as the Ethiopian World Federation, Inc., and the movement’s propaganda campaign would rest on the Voice of Ethiopia, a weekly newspaper the Bayens ran uninterrupted for several years. Writing in 1939 in the March of Black Men, a booklet published by the Voice of Ethiopia Press, Malaku would describe the Rockland Palace gathering as a milestone in Ethiopian and African American relations. “The audience went wild with joy,” he would remember, “and from that night on they have been working with me in the interest of Ethiopia and the Black Race, up to this day.”

Because of his sudden death at the prime age of forty, coupled by the insulated nature of Ethiopian studies, Malaku has yet to find his rightful place in the pantheon of Pan-African leaders. Only an authoritative biography, which is long overdue, may change that. Until that happens, however, rescuing Malaku from further erasure calls for occasional acts of commemoration. Thanks to extensive media coverage of the incident, rereading the Delano ordeal as a Gandhian turning point is an example of that.

Indeed, what happened to the medical doctor on 23 September resonates closely with the injustice suffered by Gandhi on the fateful train ride in South Africa several decades earlier. Both Malaku and Gandhi began their diaspora careers at the height of their patrician aspirations. Gandhi, British-educated Indian barrister, had traveled to South Africa to promote Indian rights; while Malaku, a U.S.-trained medical doctor and member of the young Ethiopian intelligentsia, had returned to the United States to raise funds to help his country’s war refugees. Gandhi’s epiphany took place on 7 June 1893, the day he spent a chilly winter night at the Pietermaritzburg train station, having resisted his removal from the first-class car to which his ticket had entitled him. Likewise, Malaku’s check-in at the Delano concluded with a life- changing Jim Crow humiliation, an act that stripped class pretentions and plunged him at the center of American race politics. Gandhi, a nationalist turned spiritual leader, would succumb to an assassin bullet only a few months after India’s independence. Malaku, who spent the next four years in Harlem as an antifascist crusader, fundraiser, newspaper editor, and Pan-African activist, would die in a New York State mental hospital on 4 May 1940, exactly one year before the restoration of his country’s independence.

–

About the Author:

Dr. Fikru Negash Gebrekidan is a Professor of History at St. Thomas University in Canada.

Join the conversation on X and Facebook.