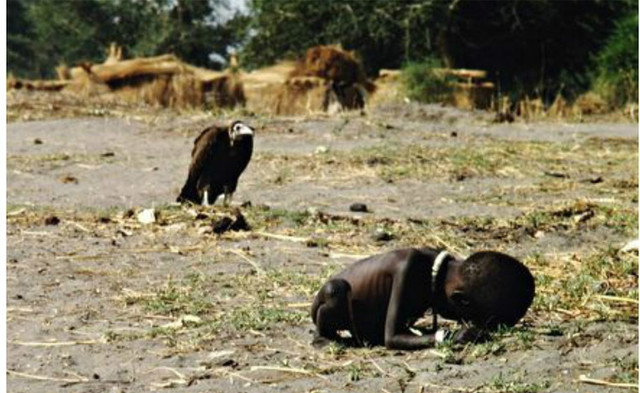

A single photo focused the world’s attention on Sudan in 93. As Gaza and MH17 dominate, Africa’s horrors remain invisible. (Photo: Kevin Carter)

A single photo focused the world’s attention on Sudan in 93. As Gaza and MH17 dominate, Africa’s horrors remain invisible. (Photo: Kevin Carter)

By Maaza Mengiste

Thursday 31 July 2014

In the photograph a little girl is hunched low, head bent to the ground, ribs jutting out from a too-small body wasting away from starvation. A few feet behind her, a vulture waits, avid and focused, for her to die. When this photograph, taken in southern Sudan in 1993 by the late photojournalist Kevin Carter, was published, the outcry from the public was immediate and visceral. Questions of ethics, and inquiries on how to help, flooded the New York Times. The Pulitzer prize-winning photo riveted the world and directed attention to the devastating famine in the country.

As controversial as the picture was, as problematic as it may have been for Carter to shoot it while the young girl sat, helpless prey to a vulture, the image sparked worldwide interest in the famine. People noticed and, suddenly, people cared.

Now, three years after independence, South Sudan, the world’s youngest country, is expected to declare that it is once again in a state of famine. The crisis has been caused by conflict between government forces and various opposition groups. Four million people are facing emergency levels of food shortages. One and a half million have been displaced and 50,000 children are at risk of death from malnutrition.

The situation has been called the most rapidly deteriorating humanitarian crisis today, but without an image startling enough to make the headlines, it has remained invisible. The world’s gaze is being directed elsewhere, towards the devastating news emerging daily from Gaza and the tragic downing of Malaysia Airlines flight MH17.

South Sudan is not the only African nation in crisis. There is also the Central African Republic and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The three cases share one striking similarity: not enough attention is being paid to what’s going on. In trying to explain why, journalists blame the lack of bureau offices outside key cities in a few countries. Some point to news outlets’ financial struggles, and the shrinking number of journalists conducting immersive stories. Time is too short, money too tight, people too few.

Read more at The Guardian »

—

Join the conversation on Twitter and Facebook.