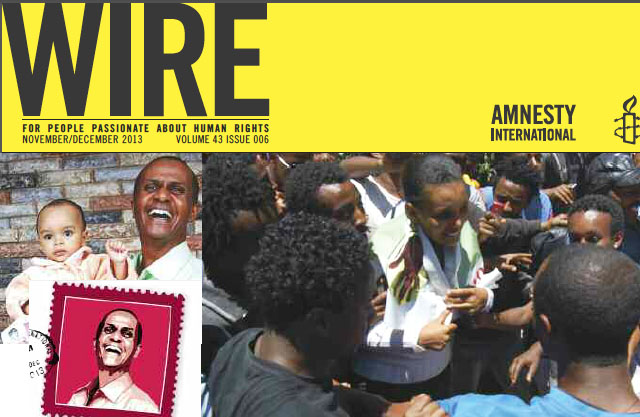

The following article is from the November/December 2013 print issue of Wire, Amnesty International's Global Magazine, published as part of a campaign for the release of Eskinder Nega. (Photo: Wire cover)

The following article is from the November/December 2013 print issue of Wire, Amnesty International's Global Magazine, published as part of a campaign for the release of Eskinder Nega. (Photo: Wire cover)

Wire: Amnesty International’s Global Magazine

Birtukan Mideksa spent years in an Ethiopian prison, and was featured in Write for Rights 2009 as a prisoner of conscience. She told WIRE what international support meant to her, and how the power of letter writing can be harnessed again this year to help her good friend, Eskinder Nega.

Birtukan Mideksa speaks to us from her desk in Boston, USA, amid the bustle of student life. A Harvard fellow, she is taking an MA in Public Administration at Kennedy School and is a thriving academic.

It’s a far cry from the Ethiopian prison cell she occupied only a few years ago – a place her friend, Eskinder Nega, knows only too well. He is currently serving an 18-year sentence because of his journalism.

In fact, the two were detained together between 2005 and 2007, alongside Eskinder’s wife Serkalem. All three were declared prisoners of conscience. They have also featured in Amnesty’s Write for Rights campaign – Serkalem in 2006, Birtukan in 2009, and this year, Eskinder, because he’s in prison again.

“I was incarcerated twice. The first time, for 18 months, the second, 21 months,” recalls Birtukan. “Look at how many times Eskinder has been imprisoned over the past 10 years – eight times. His wife, Serkalem, was also incarcerated. This is a story of thousands and millions of government opponents in Ethiopia. If you look at the pattern, it’s getting worse.”

The toughest time in prison

In 2005, Birtukan was leader of Ethiopia’s main opposition party, Unity for Democracy and Justice. Her party contested the elections that year, but lost under questionable circumstances. When she and her supporters peacefully protested against the legitimacy of the election results, thousands were arrested. Birtukan, Eskinder, Serkalem and over 100 journalists, opposition leaders and others were put on trial.

“The whole time was very difficult, especially for Serkalem,” says Birtukan, who shared a cell with her at one point.

“She was pregnant and she had to live with 70 to 80 prisoners in a very unclean cell. The smell was terrible.

“When she finally had her baby, that was one of the times I really felt low. She went to the hospital and… came back alone. She had to leave the little one with her mum. My daughter was with my mum – she was eight months old. So we consoled each other. Our major difficulties came because of our responsibilities as mothers, and our attachment to our children. That was really the toughest time in prison.”

Silver lining

Birtukan was given a life sentence, but was eventually pardoned and released after nearly 18 months in detention. Her freedom, however, was short-lived. After speaking publicly in Sweden in November 2008 about the process that had led to her release, she was re-arrested in Ethiopia on 28 December 2008. Her pardon was revoked and her life sentence re-imposed.

Amnesty issued Urgent Actions on her behalf and promoted her case in Write for Rights 2009. For Birtukan, who was kept in solitary confinement for long periods, this collective effort was a lifeline.

“In 2009, only my mum and my daughter were allowed to visit me,” says Birtukan. “I was really cut off from the whole world. I didn’t have any access to the media. We were not allowed to talk about Amnesty International’s initiatives, but my mum mentioned to me that Amnesty people were trying to advocate for me. That was like a silver lining. It gave me hope. It connected me to the real world.”

Birtukan was finally freed in October 2010. “The pressure you guys were exerting on the Ethiopian government was very instrumental in securing my release,” says Birtukan.

She hopes it will be possible to do this again, this time for Eskinder.

Sustained optimism

In 2012, Eskinder was jailed for “terrorism” after giving speeches and writing articles criticizing the government and supporting free speech.

To Birtukan, his struggle is almost heroic.

“Eskinder is one of the most virtuous people I know in my country,” she says. “He really believes in the good in all of us. It’s vivid in his personal life and in his activism. The love he has for his country, his dedication to seeing people living a dignified life – it’s really huge.

“He didn’t start his activism with just criticizing the government. He always gave them the benefit of the doubt. He was relentlessly committed to expressing his views, his ideas.”

That commitment triggered a campaign of harassment, including threats, a ban on the newspaper Eskinder ran with Serkalem, and repeated imprisonment. In 2005, when all three were jailed, Eskinder was thrown into solitary confinement for months on end. “That didn’t make him a hateful person,” observes Birtukan. “Still, he sustained his optimism and strong belief in his cause.”

Indispensible support

With its network of supporters worldwide, Amnesty’s potential to secure Eskinder’s freedom is significant, notes Birtukan. “The support we get as political prisoners is indispensible.”

But, she adds, “We shouldn’t forget the people back home – they would love to support us – but the suppression is huge. People can’t express that kind of protest against our imprisonment in an organized way.” This makes Amnesty’s support all the more crucial, she says.

It also lends legitimacy to the struggle. “Some people say fighting for rights and democracy in Africa is futile,” explains Birtukan. “Some people even try to focus on the economic performance of a country. But we mustn’t trade off our human rights for monetary benefit.

“The things you are working on – they validate and reassert those aspirations and those rights we have as human beings as inviolable, no matter what. It has huge significance in terms of the moral support you generate for activists like Eskinder and myself.”

—

Related:

Taking Eskinder Nega & Reeyot Alemu’s Case to African Court on Human Rights (TADIAS)

Join the conversation on Twitter and Facebook.