Then-President Barack Obama and his national security adviser, Susan Rice, at the Group of 20 summit in Antalya, Turkey, in 2015. (Getty Images)

Then-President Barack Obama and his national security adviser, Susan Rice, at the Group of 20 summit in Antalya, Turkey, in 2015. (Getty Images)

The Washington Post

By David Ignatius

Reading Susan Rice’s new memoir, “Tough Love,” is a reminder of two things: what a remarkably gifted, subtle but maddeningly distant man President Barack Obama was; and how people such as Rice who served him endured ceaseless public attacks in a country that was already on the ragged edge, though we didn’t yet know it.

Washington memoirs are most valuable for the parts that aren’t about what the author did at the office. That’s especially true of this account by the former national security adviser. The riveting passages are where Rice tells the private story that was hidden: her parents’ brutal divorce, her mother’s death, her children’s struggles with their mother’s public vilification.

Good memoirs always have a quality the Germans define as a bildungsroman, a novel of the principal character’s education in the world. That’s true with Rice’s tale: She was an African American who triumphed in the elite world of prep schools, Ivy League colleges and Rhodes scholarships. She embodied the intellect and ambition these institutions aspired to produce, even as she masked a shattered family where her parents “fought ugly and often,” she writes, and her home life was “like a civil war battlefield.”

—

Related:

Susan Rice Has Spent Her Career Fighting off Detractors: ‘I inadvertently intimidate some people, especially certain men’ (WaPo on Her Memoir)

Former national security adviser Susan Rice at her Washington home. (The Washington Post)

The Washington Post

October 8th, 2019

Susan Rice has spent her career fighting off detractors: ‘I inadvertently intimidate some people, especially certain men’

She should have listened to her mother.

“Why do you have to go on the shows?” Lois Dickson Rice asked her daughter, Susan, in September 2012 “Where is Hillary?”

Susan Rice was then the United States ambassador to the United Nations, equipped with a gold-standard Washington résumé — Stanford, Rhodes scholar, Oxford doctorate, former assistant secretary of state for African affairs. She explained that Secretary of State Hillary Clinton was “wiped after a brutal week.” The Obama White House asked Rice to appear “in her stead” on all five Sunday news programs.

It was days after attacks in Libya killed four U.S. officials.

“I smell a rat,” said her mother, a lauded education policy expert. “This is not a good idea. Can’t you get out of it?”

“Mom, don’t be ridiculous,” Rice said. “I’ve done the shows. It will be fine.”

Well, no, it was not.

Benghazi became the millstone in Rice’s stellar career. It stopped her from succeeding Clinton.

Criticism of Rice was relentless… The scrutiny lasted through multiple congressional investigations.

The aftermath took a punishing toll on Rice’s family and professional reputation, she reveals in her frank new memoir, “Tough Love.” The book also explores how, despite Rice’s many accomplishments during two administrations, she attracted criticism for her brusque manner. And Rice faces an extra challenge — she’s been forced to grapple with whether any of this adversity was somehow a result of her race and gender.

“The combination — being a confident black woman who is not seeking permission or affirmation from others — I now suspect accounts for why I inadvertently intimidate some people, especially certain men,” she writes, “and perhaps also why I have long inspired motivated detractors who simply can’t deal with me.”

Read the full article at www.washingtonpost.com »

—

Related:

What My Father Thought Me About Race: By Susan Rice

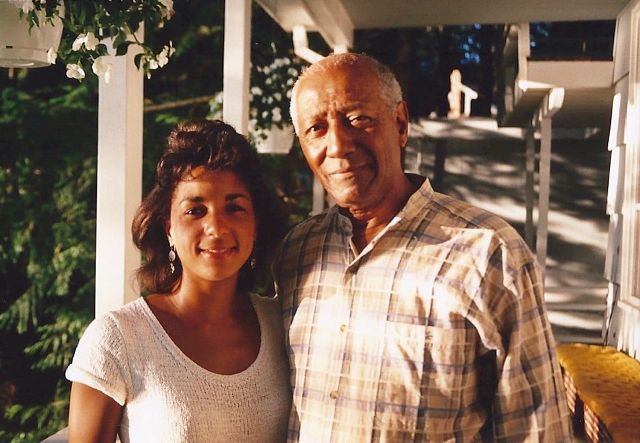

Susan E. Rice, the national security adviser from 2013 to 2017 and a former United States ambassador to the United Nations, is a contributing opinion writer for The New York Times. She is the author of the forthcoming memoir, “Tough Love: My Story of the Things Worth Fighting For,” from which this essay is adapted. (Photo: Susan Rice with her father Emmett J. Rice, right, and the Federal Reserve chairman, William Miller, in 1979. (Getty Images)

The New York Times

By Susan E. Rice

My father, Emmett Rice, was drafted into military service at the height of World War II and spent four and a half years in uniform, first as an enlisted man and ultimately as an officer with the rank of captain. Called up by the Army Air Force, he was sent to a two-part officer training program, which began in Miami and was completed at Harvard Business School — where he learned “statistical control” and “quantitative management,” a specialized form of accounting in an unusual program designed to build on his business background.

Emmett eventually was deployed to Tuskegee, Ala., where he joined the famed Tuskegee Airmen, the nation’s first black fighter pilot unit, which distinguished itself in combat in Europe. Though he learned to fly, my father was not a fighter pilot, but a staff officer who ran the newly created Statistics Office, which performed management analyses for commanding officers. He earlier served a stint at Godman Field adjacent to Fort Knox, Ky. There, he was denied access to the white officers’ club. To add insult to injury, he saw German prisoners of war being served at restaurants restricted to blacks. Both in the military and the confines of off-base life, his time in Kentucky was a searing reintroduction to the Southern segregation he had experienced as a child in South Carolina.

Susan and Emmett Rice in 1996. (Credit Ian Cameron)

Still, socially and intellectually, dad’s Tuskegee years were formative. He met an elite cadre of African-American men who would later be disproportionately represented in America’s postwar black professional class, among them my mother’s brothers, Leon and David Dickson. Dad’s Tuskegee friends and acquaintances formed a network he maintained throughout his life. What was it, I have often wondered, about those Tuskegee Airmen and support personnel that seemingly enabled them to become a vanguard of black achievement? Perhaps the military preselected unusually well-educated and capable men for Tuskegee, or some aspect of their service experience propelled them as a group to succeed. To my lasting regret, I failed to take the opportunity to study this topic in depth before almost all those heroes passed away.

Read the full article at nytimes.com »

—

Join the conversation on Twitter and Facebook.