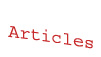

Dr. Yohannes Haile-Selassie, one of Ethiopia’s leading paleoanthropologists and the director of the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University (ASU) in the US, reflects on Lucy’s legacy at 50 and advocates for decolonizing the narrative of human origins. (Photo: Alamy)

Dr. Yohannes Haile-Selassie, one of Ethiopia’s leading paleoanthropologists and the director of the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University (ASU) in the US, reflects on Lucy’s legacy at 50 and advocates for decolonizing the narrative of human origins. (Photo: Alamy)

Tadias Magazine

November 22nd, 2024

TADIAS (New York) – As we approach the 50th anniversary of Lucy’s discovery—a pivotal moment in our understanding of human origins—the conversation shifts to the often-overlooked contributions of African scientists. Ethiopian paleoanthropologist Dr. Yohannes Haile-Selassie, director of the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University, has been at the forefront of reshaping this narrative.

Dr. Haile-Selassie, whose groundbreaking fossil discoveries include Ardipithecus kadabba and Ardi, emphasizes the need to “decolonize paleoanthropology.” He advocates for more African-led research and infrastructure to give local scholars and institutions an equitable role in telling humanity’s story.

“Western scientists can’t continue this ‘helicoptering in and out’ approach to fossil discovery,” he warns, urging collaboration and sustainable practices to empower African institutions and researchers.

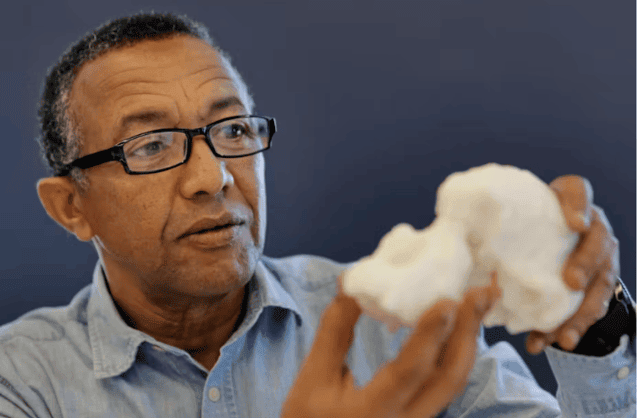

Schoo children inspect the fossilized bones of Lucy, on display at the National Museum of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa. (Xinhua/Alamy Stock Photo)

For a deeper dive into Dr. Haile-Selassie’s insights and the movement to redefine the field of paleoanthropology, read the full feature on The Conversation: Fifty years after the discovery of Lucy, it’s time to ‘decolonise paleoanthropology’ – podcast.

From The Conversation

‘Deep inside, something told me I had found the earliest human ancestor; I went numb’ – Yohannes Haile-Selassie on his lifetime quest to discover ancient humanity

Yohannes, you were a 14-year-old schoolboy in Ethiopia when Lucy was discovered. What are your memories of this landmark moment in your country’s history?

In fact, on the day Lucy was found – Sunday, November 24 1974 – Ethiopians woke up to some other devastating news. The previous night, Ethiopia’s military regime had executed more than 60 ministers and generals of Emperor Haile-Selassie’s regime. The announcement of Lucy’s discovery probably came up later that week, but I doubt many people paid attention to it amid all the turmoil, with the military regime taking control of Ethiopia.

Personally, I have no recollection of the announcement of Lucy’s discovery. I grew up in a Christian family, so as far as I knew at that time, it was God who created humans and I wouldn’t have understood the significance of Lucy.

Of course, over time, her discovery brought the idea of Ethiopia as a “cradle of mankind” to the forefront of public consciousness around the world. With that came national pride – today, Ethiopia brands itself the “land of origins”. Lucy played a big part in that.

Yet even now, the narrative of ancient human discovery appears to omit many of the African researchers and institutions that played key roles in this story?

Many of the fossils that made western scientists famous were actually found by local Africans, who were only acknowledged at the end of a scientific publication. For a long time, African scholars were never part of telling the human story; nor could they actively participate in the analysis of the fossils they found. Up to the 1990s, long after Lucy was found, we were only present in the form of labourers and fossil hunters.

So, when we celebrate the 50th anniversary of Lucy, we shouldn’t forget that a reappraisal of the role of African scientists in our understanding of ancient humans is long overdue. Specifically, we need to decolonise paleoanthropology.

–

Join the conversation on Twitter and Facebook