Above:Church, Mädhane Aläm at Mäjate, Ethiopia, 1892-1893; Private Collection, France, before 1973; Sam Fogg, London; Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore, 1998, by purchase.

New York, NY — The Museum of Biblical Art examines the exhilarating artistic heritage of one of the world’s oldest Christian kingdoms in Angels of Light: Ethiopian Art from the Walters Art Museum, opening Friday, March 23, 2007.

For the showing, towering metalwork crosses, brilliantly colored icon paintings, decorated manuscripts, and other rare objects have been drawn from one of the largest and finest collections of Ethiopian art outside of Addis Ababa—that of the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland.

Angels of Light covers a vast sweep of time, from the 4th century, when Ezana, the King of Aksum, converted to Christianity, to the 19th century. Altogether, 44 masterworks speak to the manner in which Ethiopian artists infused their works with a unique sense of form and color, continually absorbing and transforming influences from other cultures.

“Ethiopia’s artistic heritage defies expectation, blending Semitic oral traditions and African colors and patterns with Italian narratives and Byzantine icon forms. I believe that many visitors will be amazed by what they see, from the hot yellow and red colors of the painted icons to the dramatic processional crosses, draped in fabric,” says Ena Heller, director of MOBIA.

Ethiopian culture has deep roots: the first Ethiopian emperor is even said to have been the son of the Queen of Sheba and King Solomon. According to tradition, it was he, Menelike, who brought the Ark of the Covenant to the country from Jerusalem, thus crowning Ethiopia as the new Israel.

“Today, too often we forget that Ethiopia was a world power, along with Rome and Persia, for much of the first millennium of the common era,” says Gary Vikan, Director and Curator of Medieval Art at the Walters Art Museum. “The Walters’ collection of Ethiopian art is a relatively new addition to the Museum—initiated only in 1993. Yet the power of these objects has already earned them an invaluable place in the story we tell of the cultures of Eastern Orthodoxy, alongside the Byzantine, Greek, and Russian cultures.”

By the 15th century, Ethiopia had developed a tradition of icon painting that rivaled the production of icons in Byzantium and Russia, and the new kind of painting emerging in Renaissance Italy. Representing this high point in the history of Ethiopian art in Angels of Light are nine rare panel paintings, diptychs, and triptychs, each representing a distinct style or iconology. One is a large tempera on panel called “Our Lady Mary with Her Beloved Son and Archangels Michael and Gabriel,” which is thought to have been created by a painter of the royal court between 1445 and 1480. The artist suggests an easy, human affection between Mary and Jesus in the way he depicts the pair locked in a rapt gaze and holding hands, encircled by folds of cloth. The choice of the Virgin and Child as a subject here, and the use of forms familiar from Byzantine or Italian models, confirm that Ethiopian artists were aware of Western traditions. Even more directly linked to the art of the Mediterranean is a triptych painted approximately 200 years later, depicting the Virgin and Child flanked by the archangels and scenes from the life of Christ, the apostles, Saint George, and Saints Honorius, Täklä Haymaont, and Ewostatewos. The central panel is based on a famous icon from the Roman basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore that was believed to have been painted by Saint Luke the Evangelist.

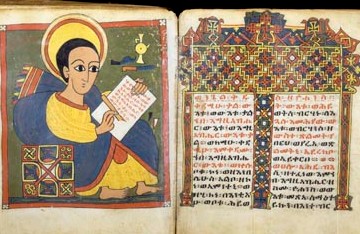

The illuminated books and scrolls in Angels of Light are especially powerful reminders of the passionate faith of medieval Christians in Africa. In particular, a pair of illuminated charts dating to the late 14th century or early 15th century bring to light an exercise of scholarship and devotion that seems mind-boggling in today’s “Google” age. On a single sheet of parchment, framed by classical arches surmounted by birds, the Canon Tables provided priests with an early cross-referencing system to reconcile the different accounts of Christ’s life. Also in this section of the exhibition is a 16th-century gospel book, in nearly pristine condition, which features full-page portraits of the Evangelists painted in bright bold color and an assured line.

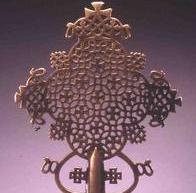

Eight medieval bronze processional crosses will be stationed together in the MOBIA gallery, their varied geometric patterns offering a delight to the eye and mind. Meant to be seen against the sky or by candlelight, their abstract shapes are a hybrid of Byzantine and Islamic forms, incised, perforated, welded, and /or cast by master artisans. In one cross from the late 12th or early 13th century, the sign of Christ, as described in the Gospel of Matthew, can be made out in the curved abstracted form. Upon close inspection, 13 small crosses emerge from a seemingly unbroken weave of tiny interlocking circles in a 15th-century staff.

Ideally situated near the Red Sea, and encompassing one of the branches of the Nile river, Ethiopia was able to establish strong ties in both trade and religion with nations around the Mediterranean Sea. A prayer book with its worn leather satchel, a parchment scroll in its leather carrying case, folding icons (diptychs) and small books speak to the benefit of a portable gospel faith in a cosmopolitan center of trade.

Learn More at The Museum of Biblical Art